2017 may

go down in history as the year when it frst became clear that the fossil fuel

era was fnally starting to sputter to an end. The cost of new solar and wind

power started to fall below the price of new coal and gas plants in a growing

number of regions. The CEO of NextEra Energy, one of the largest electricity

producers in the US, now predicts that “early in the next decade” — just a few

years from now — power will be cheaper from unsubsidized new wind and solar

plants in the US than from existing coal and nuclear plants. It’s still far from game over for the

fossil fuel industry, but the game hasdrastically changed.

In the “old days” of early 2017, the argument could still

legitimately be made that yes, intermittent renewables are getting cheaper, but

they are still intermittent – solar output crashes when the clouds roll in, and

wind turbines are just sleek sculptures on a calm day. Long term energy storage

and large scale battery storage were touted as the missing link. But the commissioning

of a 100-megawatt grid-connected battery in South Australia in late November

2017, only 100 days after it started construction, was a stunning illustration

that large-scale battery storage is now economically and technically feasible.

On the transportation front, China, India, the United

Kingdom, France, and California all announced efforts to accelerate the adoption of electric cars and

phase out internal combustion engines. These efforts have led analysts to bring forward their projections

for the date when global oil consumption peaks and then starts its permanent

decline. In July 2017, Goldman Sachs forecast that global oil demand could peak

as early as 2025. While oil company scenarios are unsurprisingly still mostly

in denial about the likely speed of the energy transition, even ExxonMobil

admitted in early 2018 that the Paris Agreement meant that oil consumption

could easily drop by 20 percent between 2016 and 2040 — and might even be cut

in half.

Tightening the Financial Screws

While

these technical and economic developments are hugely signifcant for the demand

side of the clean transition equation, developments in 2017 that will constrain

financing for dirty energy supply were equally game-changing. Most fossil fuel companies

don’t have the billions in cash it takes to reach, produce, and transport

fossil fuels without the support of big banks. Banks are central actors in how

this transition will play out.

In June,

Dutch bank ING clarifed an existing tar sands policy by ruling out project fnance

for tar sands production and transport, explicitly excluding pipelines such as

Keystone XL. Later in the year the bank announced it would phase out lending to

any utility with more than 5 percent of its power coming from coal. In October,

French bank BNP Paribas made an even more ambitious commitment to move away from

extreme oil and gas fnancing (see page 23).

Two

months later at the One Planet Summit in Paris, the trickle of fnancial

institutions restricting their fnance for fossil fuels grew into a fast-flowing

stream. The World Bank announced it would no longer fnance oil and gas

extraction after 2019. French insurance giant AXA landed a huge blow to the

fossilfuel industry with a commitment to cease insuring tar sands production

and pipelines and new coal mines and power plants. AXA will also divest nearly

$4.5 billion from tar sands and coal companies. At the same summit, other major

French banks announced further restrictions on their support for tar sands.

The

progress made in Paris rapidly crossed the oceans. Before the end of 2017 the

governor of New York promised to cease state pension funds’ investments in

entities “with signifcant fossil-fuel activities.” Then in January 2018, Mayor

Bill de Blasio held a press conference in a community center that had been flooded

by Hurricane Sandy, and announced that New York City pension funds’ existing

partial divestment from coal would be extended with a target to divest their $5

billion in holdings in a range of fossil fuel companies.

In

February 2018, the University of Edinburgh announced that its endowment — the

third biggest educational endowment in the U.K. — would dump its stock in oil

and gas companies. The endowment had already divested from coal and tar sands —

as have the other two biggest university endowments, for Oxford and

Cambridge.14 The University of Edinburgh has not been the only investor to

withdraw from the worst of then fossil fuels and then, under continued activist

pressure, and presumably because they realize that getting out of fossils

hasnot caused them any signifcant fnancial harm, withdraw fromthe whole fossil

fuel sector.

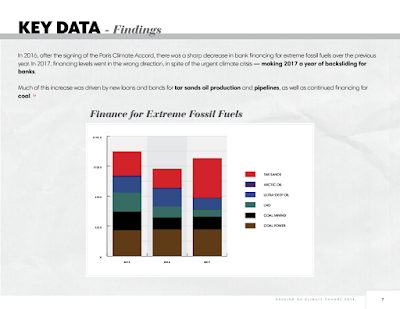

Stuck in the Tar Sands

However, all this positive technological and fnancial

sector news over the past year is not reflected in the top-line numbers on bank

funding in this report card. On the contrary, the $115 billion in bank support

for the largest extreme fossil fuel companies in 2017 is 11 percent higher than

in 2016. But a closer look at the data reveals that this uptick is entirely due

to a whopping 111 percent increase in bank lending and underwriting to tar

sands extraction and pipeline companies and projects in the past year. Strip

out the tar sands numbers,and bank support for the extreme fossil sectors

continued its rapid decline, dropping 17 percent over the past year to $68 billion.

Banks did not suddenly decide in 2017 that tar sands oil

is a great long-term prospect. Rather, the increase in funding was in large

part to fnance the purchase by pure-play Canadian tar sands companies of the tar

sands reserves of the oil majors. Companies including Shell, ConocoPhillips and

Statoil ofoaded more than $23 billion in Canadian assets in 2017, in order to

focus on lower cost reserves elsewhere. Another factor driving up the tar sands

numbers for the biggest global banks in 2017 was $3 billion for Kinder Morgan

toward the costof the highly disputed Trans Mountain pipeline from Alberta

tothe British Columbia coast.

The massive hike in bank support for tar sands in 2017 —

to nearly $47 billion — led this sector to overtake coal power, the best funded

of the extreme fossil sectors in 2016. Overall support for coal power has stayed

just about stagnant in the last three years. And yet, though the Chinese banks

are the biggest funders of coal power, the data show an increase in non-Chinese

coal fnance over the past three years. This continued support comes despite

numerous banks adopting policies that limit their coal project fnancing,

because these policies fall short of restricting coal power fnancing in what are

increasingly its most common geographies (developing countries) and forms

(general corporate fnance).

Coal mining saw a small increase in bank support in 2017

(up 5 percent). However this came after a sharp 38% drop between 2015 and 2016.

This drop is presumably because many banks adopted policies restricting support

for coal mining around the time of the Paris climate conference. In 2017, two

thirds of all support for coal mining came from the four big Chinese banks —

and yet it is the Western banks whose coal mining fnancing trend shows a

dangerous resurgence upward.

Bank support for liquefed natural gas (LNG) terminals in

North America has fallen 62 percent since 2015 — far more thanfor any other

sector over the last two years. The fracking boomover the past decade led to a

rush of dollars being spent onLNG facilities to export surplus natural gas from

the United States. However, other countries, especially Australia and Qatar, also

spent big on LNG facilities, so the LNG capital investment boom has been

followed by a bust as the world now has surplus LNG production facilities.18

Whether this is a permanent bust or a temporary setback will be seen in the

coming years, as the fate of the more than 50 proposed North American LNG

export terminals is determined and global banks decide whether or not to

support these stranded assets in the making.

“When,” Not “If ”

The Paris Climate Agreement, for which many global banks have

declared their support, sets an ambition of keeping global warming to “well below

2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels,” with the aim of limiting warming

to 1.5 degrees Celsius.20 The U.N. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change

(IPCC) will publish a report in September 2018 summarizing the implications of

the Paris Agreement’s more ambitious goal.21 A leaked draft of the report is, to

say the least, sobering. The world has already warmed by a degree, and another

half degree means much more disruption, including “fundamental changes in ocean

chemistry” from which it may take many millennia to recover, as well as floods,

droughts, deadly heatwaves, food shortages, migration, and conflicts. Two

degreeswill of course be much worse. Moreover, the IPCC’s draft reportstresses

that keeping below two degrees is a gargantuan task, even with “rapid and deep”

reductions in greenhouse gas emissions.

The game-changing developments in the energy sector in

2017 affirm that the question is not if, but when the fossil fuel sector goes

into terminal decline. But the date of the “when” has existential consequences

for people, societies and ultimately much of life on earth. While 2017 saw much

encouraging progress on clean energy, it also saw a terrifying escalation of hurricanes,

fres, and floods. These offer stark evidence of

just how much is at stake and just how ethically unacceptable it is for banks

to keep funding the fossil fuel industry’s expansion.

No comments:

Post a Comment