Achieving the goals of the Paris

Climate Agreement will require action across all sectors of the economy, and

the finance sector is clearly fundamental. In fact, one of the Paris

Agreement’s three objectives is “making finance flows consistent with a pathway

towards low greenhouse gas emissions and climate-resilient development. Recent

announcements by some of the world’s largest financial institutions reveal an

emerging consensus that all fossil fuel investment and financing risks both

climate security and economic value. The finance sector has an important role

to play in ending further exploration and the expansion of fossil fuel

production.

Last December, at the One Planet

Summit in Paris, the World Bank announced that it would no longer fnance oil

and gas extraction after 2019. To date, no other international financial

institution has this kind of commitment on its books, but for how long?

The World Bank’s decision to cease

funding oil and gas extraction sets a standard to be matched and bettered. When

the World Bank established a policy to restrict coal financing in 2013, dozens

of other institutions — public andprivate — followed suit. But the World Bank

is not the only government-controlled fnancial institution to shun fossil fuel

investment. Norway’s central bank has proposed to the fnance ministry that the

country’s trillion-dollar sovereign wealth fund, the Government Pension Fund

Global, sell off its oil and gas

stocks. City and municipal pension funds across the United States and beyond

are already doing this, as is the Republic of Ireland.

In December 2015, world governments

agreed in Paris to limit global average temperature rise to well below 2

degrees Celsius, and to strive to limit it to 1.5 degrees Celsius. In September

2016, Oil Change International released a seminal report, The Sky’s Limit, Why

the Paris Climate Goals Require a Managed Decline of Fossil Fuel Production.38

The report analyzed what a Paris-aligned carbon budget would mean for fossil

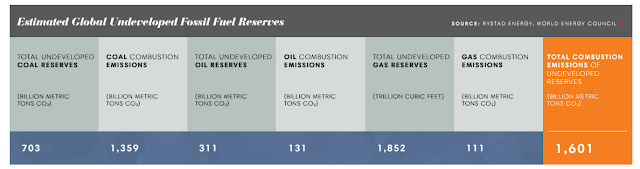

fuel production globally. The key fndings, shown in the graph, include:

·

The potential carbon emissions

from the oil, gas, andcoal in the world’s currently operating felds and mines

would take us beyond 2 degrees Celsius of warming.

·

The reserves in currently

operating oil and gas feldsalone, even with no coal, would take the world

beyond 1.5egrees Celsius of warming.

As such, exploration for and expansion of new reserves

areincompatible with the Paris climate goals. Additionally, someproduction will

require a managed decline faster than naturaldepletion rates, such that some

reserves are not fully extracted.

Given that the fossil fuel reserves delineated in this

chart are entirely within oil, gas, and coal mines and felds that are currently

producing or under construction (at the time of publication), development of

new production is incompatible with Paris-aligned carbon budgets. Despite this,

the global oil and gas industry today holds around 311 billion barrels of oil

and 1.8 quadrillion cubic feet of gas in projects that are as yet unsanctioned

(that is, the operating company has not yet made a fnal investment decision on

the project) and still spends over $60 billion annually exploring for

more.Sanctioning and combusting all the currently unsanctioned oil and gas

reserves would add over 240 billion metric tons of CO2to the

planet’s atmosphere. Any fnance provided to oil and gas companies that enables

these reserves to be extracted and burned goes beyond the limits set by the

Paris goals. Financing expansion into these reserves, or those acquired through

ongoing exploration, is financing climate disaster.

While both developed and undeveloped coal reserves are

vast, the pace of production decline is slow, and only a handful of misguided

plans to open new mines remain. Projects such as the Carmichael coal mine in

Australia (see page 56) struggle to fnd fnancing amid the interrelated

pressures of climate policy and market decline. It is the oil and gas sector

that is still aggressively pushing for expanding extraction despite clear

signals that it is time to stop digging.

With the potential emissions of currently in-production

reserves already exceeding our carbon budgets, the carbon intensity of one

fossil fuel source compared to another cannot be considered a sufcient

criterion for judging whether an investment is compatible with climate action.

The expansion of any fossil fuel production fails that climate-compatibility

test.

While ending expansion of the fossil fuel sector is

critical, it will also be necessary for some existing production to be phased

out in a managed decline. Though this will be a challenge for many companies

and nations dependent on fossil fuel production and consumption, a carefully

managed decline and a just transition for workers and communities is far

preferable to an unmanaged decline if necessary action is ignored or delayed.

This is why nearly 500 organizations and ofcials from more than 70 countries

have signed the Lofoten Declaration calling for a halt to fossil fuel

development and a managed decline of existing production.

Climate leadership is being redefned, and the fnance sector

has an opportunity to recognize, adapt, and even lead in the transition away

from the fossil fuel era. In order to do so, banks must put an urgent end to

fnancing fossil fuel expansion of all kinds, and ultimately plan for a

decarbonization of their entire portfolios in line with global climate goals.

DOWNLOAD E-BOOK CLICK HERE

No comments:

Post a Comment